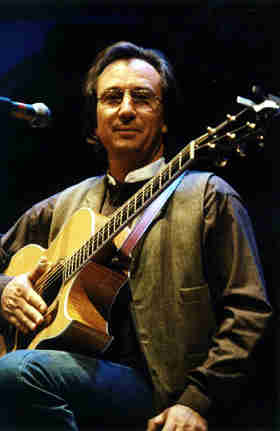

- Jim Messina

- Your Daddy Does Rock ‘n Roll

- (and Teaches, Too)

By Mark T. Gould

It is a safe bet to say

that an almost 51 year old former rock star, with years of playing to sold out crowds in

arenas and stadiums, might be bemused with the reaction of a roomful of older, devoted

fans mixed with half-listening high rollers, but for Jim Messina, the sound of middle-aged

music mixes well with the clanging of slots and the din of high rollers.

It is a safe bet to say

that an almost 51 year old former rock star, with years of playing to sold out crowds in

arenas and stadiums, might be bemused with the reaction of a roomful of older, devoted

fans mixed with half-listening high rollers, but for Jim Messina, the sound of middle-aged

music mixes well with the clanging of slots and the din of high rollers.

"I’m just now feeling good about performing

and singing again," a trim, introspective Messina said recently, following a mid-week

performance at the Mohegan Sun Casino’s Wolf Den. "My goal is to continue to

work and write. The performance aspect of this keeps me healthy and feeling young. I have

a young son, and I hope he can see my legacy and be proud of it."

Legacy indeed. At the age of 19, Messina, a staff

engineer, found himself directing the studio energies of Stephen Stills, Neil Young and

Richie Furay at the demise of the legendary Buffalo Springfield, becoming a member during

the recording of their final album, "Last Time Around." Within a year of that

debacle, he, along with Furay, formed Poco, arguably the first and best of the seminal

country-rock bands emerging from Southern California in the late Sixties. Ironically,

while both are cited as major influences for musicians since that time, neither made it

big commercially, which may have made sense for Messina’s growth at the time.

"In the Springfield, I wasn’t even thinking

about commercial music," he said. "I was worried about engineering and

producing, getting Richie, Neil and Stephen on tape, which was a challenge at age 19. I

had no ego then. It made things easier.

"When Poco started, I’ve never said this

before, but now Richie’s published a book (a history of the Springfield with

co-author John Einarson), and you can read his words and feel his frustration,"

Messina said, "Richie wanted commercial success in both bands. With Poco, he wanted

to be as big as Crosby, Stills& Nash."

"I’m not saying that’s right or wrong,

but there were, and are, no guarantees in the music business. To think that way was a

sabotage of every aspect of what we were trying to do. You should never expect that you

will get what you want. Just keep doing it and you will get better, that’s all."

To Messina, Furay’s disappointment led to his own

frustrations, and his ultimate departure from what he later termed "my first

love."

"I became frustrated because Richie was

frustrated," Messina recalled. "This was the one guy in the band who I loved,

and I still do love, who I looked up to, and admired, and I just could not understand his

behavior. That behavior scared me, and I had to get out of the way."

So, only two albums into the group, Messina left, after

a seven month indoctrination for new guitarist Paul Cotton. "I didn’t want

to leave the guys in the group in the lurch," he said. "I said I had to go, but

I wanted it to be a smooth transition."

Following Poco, Messina again worked as a staff

engineering and producer for Columbia Records, until he was introduced to a new act that

Columbia thought Messina, with his experience and know-how in the studio and out, could

nurture along.

The fellow was Kenny Loggins.

"To tell you the truth, I had mixed feelings when I

first met Kenny," Messina recalled. "I thought he was too ragged and scattered,

that he did not have enough experience. So, I put him through a rough test. I had him over

to my house, handed him an old guitar out of my closet and said ‘play me your best

songs.’

"He did it. It was clear he had the songs, the

ability, the gift. I knew it would be a lot of work to get him up to the standards of the

people I had been playing with, but I knew that he wanted to be successful. It was worth

it, but I think it put a real spin on Kenny that he’s never recovered from."

The new duo, Loggins & Messina, was all over the

radio and concert halls in the mid Seventies, with such hits as "Your Mama Don’t

Dance," "My Music," "Danny’s Song," and "House at Pooh

Corner," many of which Messina still performs in his shows. By the latter part of

that decade, an amicable split accorded between the two men, and Messina then left the

public eye, but for a fairly good reason.

"It probably hurt me in the long run," he

said," but I told Warner Bros and Columbia and everyone else that I did not want to

work with anyone with a drug or alcohol problem. Thankfully, Kenny did not have one. I

just didn’t want to be in the studio for hours, waiting for someone to lay down a

drum track.. Drugs were taking over at that time, and I really didn’t want any part

of that. I’m sure that it lost me a lot of work.."

So, he was content to release a series of solo albums,

none of which sold very much on the market, and, in the late 80s, participated in what

amounted to a three year reunion with the original five members of Poco. After that, it

was a hiatus from performing on a consistent basis, until he realized what audiences were

looking for, in essence just what his legacy was.

"When I started performing again in the Nineties, I

realized that the people who supported me and came to hear me really liked to hear the

older songs. There was really no reason not to perform them."

That realization led to the "Watching the River

Run" album, released last year on River North Records. Combining songs from each

facet of his career, and mostly cut live in a Nashville studio, the record is a bouquet of

sorts to Messina’s fans.

"Who I am is so important," he said, "and

many people who come out to the shows only see the past, so it makes sense to let them

enjoy it. I’ve got my own arrangements, style and keys for these songs, the originals

aren’t totally me, so that’s what we do."

In addition to his new-found interest in live

performances, Messina has also begun a songwriters’ workshop near his home in Santa

Barbara, California. There, he helps instruct writers in getting in touch with themselves

emotionally, but with an interesting twist.

"Psychologists call what we are after the ‘meta-state,"

he explained. "We try to get the writers to stand back and observe themselves

participating in life experiences. I can assist writers with getting into their emotional

body or being. It helps create a way to observe their own emotional states." He even

has allowed the approach to affect his own songwriting, as a new tune, "Anglers &

Wranglers," performed at this recent show, mixes Western allegory with personal

experience.

Still, it remains the interaction between Messina as a

stage performer and his audience that keeps him going now. At the Wolf Den, he was

breezily confident on stage, mixing interesting stories about his songs, jokes about

working a casino show and a lengthy history of songs that nearly the entire audience

recognized at the sound of the first notes. Again, it’s back to his legacy,

particularly for his young son.

"I became a father at 45, which is

interesting," he said. "I want my son to be able to see what I did as a young

man, and what I am doing now. I want him to be proud of it."

It is a safe bet to say

that an almost 51 year old former rock star, with years of playing to sold out crowds in

arenas and stadiums, might be bemused with the reaction of a roomful of older, devoted

fans mixed with half-listening high rollers, but for Jim Messina, the sound of middle-aged

music mixes well with the clanging of slots and the din of high rollers.

It is a safe bet to say

that an almost 51 year old former rock star, with years of playing to sold out crowds in

arenas and stadiums, might be bemused with the reaction of a roomful of older, devoted

fans mixed with half-listening high rollers, but for Jim Messina, the sound of middle-aged

music mixes well with the clanging of slots and the din of high rollers.